A Malawian Wedding Under a Baobab Tree

I once read that if you want to know and understand a people, you should look at how they deal with births, deaths, and weddings. [Side note: If you know who said that, please let me know!] On Sunday, I had the chance to photograph my first Malawian wedding.

I hadn’t received an invitation, but the owners of the lodge at which I’m staying received one. They couldn’t make it, but they assured me that I wouldn’t be turned away for gate crashing. Actually, they told me that the wedding party would most likely be honored that a photographer wanted to document their celebration.

Nisar, the owner of the lodge I’m staying at, showed me the invitation. It listed a day and a place, but there was no specific time. On the morning of the wedding, I woke at my usual hour, showered, dressed, prepared my gear, and had breakfast. It was still fairly early, but some of the staff had already left for the wedding. Nisar was letting them borrow an oversized truck so they could drive people from nearby villages to the party. I wanted to catch a ride with them, but they had left much earlier than I expected.

Nisar gave me a ride to where the party would be held. Luckily, the truck was still there. When I arrived, two of the staff from Nisar’s lodge greeted me and told me that I should sit in the vehicle. No sooner had I climbed into the cab of the truck when they decided that it was time to begin picking up the party-goers from the other villages.

The truck roared to life, and we were off. The driver honked the horn at nearly every pedestrian we passed, waving and sometimes sticking his head out the window to call out greetings. A few minutes into the ride, he took a swig out of a brown bottle, which I easily recognized to be a bottle of beer. Throughout the ride, he finished two full bottles. I was not happy about this, but I wasn’t about to start preaching the dangers of drunk driving, especially before 9am! (Drunk driving is illegal in Malawi, but I have often heard locals laughing and trading stories to see who had had the closest near-death experience due to driving while very intoxicated.)

A few minutes down the road, we stopped so one of the drivers could talk to the police. The inspection and insurance stickers on the truck were long expired, but we were “only” transporting people to and from the wedding, so the guys wanted to let the police know in hopes of avoiding any trouble. While we waited, Kenneth, one of the drivers, tried to teach me more Chichewa. He taught me the words for body, eyes, nose, mouth, ears, shirt, jeans, and shoes. The word for shoes, sapados, which is very close to the word in some latin languages, came in handy later on in the day.

When the main driver climbed back into the truck, we continued on our way, driving for ten minutes on paved roads before turning off onto a dirt road and driving for another twenty minutes. The dirt road seemed to go on and on forever! It was terribly bumpy from having been washed out in many places by heavy rains and flash floods. There were a lot of bicycles on the road, which was dangerous because the single lane was so narrow that plants hit both sides of our truck for most of the drive. The bicyclists had to jump off and stand in the bushes while we passed.

We ended at a whitewashed mosque, stopping for a half hour to wait for the passengers. It took only a few seconds before I heard shouts of “Mzungu! Mzungu!” and the sound of bare feet running towards the truck. Once the children got within a handful of yards from me, they hid behind trees and bushes to watch me. Some of the older children boldly came up to the truck to inspect me, which quickly emboldened the younger kids as well.

Kenneth translated for me. He said that many of the children had never seen a mzungu (white person) before, so they were trying to determine my gender. That was very strange for me to hear, especially since I have a very feminine appearance and voice.

Finally, a group of people emerged from around the bend in the road. They climbed into the back of the truck carrying their best shoes and special handmade flags decorated with verses from the quran. Kenneth is a Christian, so he was quick to point out the differences he saw in the Muslims, particularly their singing. Kenneth said he didn’t like their songs because he couldn’t understand the words, which were sung in Arabic.

The people in the back of the truck sang as we headed towards the wedding. The children pressed their faces against the window that connected the back of the truck to the cab, where I was sitting. When I would turn to look at them, they would hide behind the legs of the adults.

We made a few more stops in other villages along the road back to pick up more guests. The singing got louder as more people filled the back and louder still as we approached the wedding party.

The party was taking place in a group of houses around where the bride lived. When the truck pulled up, the passengers jumped off and separated themselves along their age and gender. The men went to sit under a tree to talk with the religious leaders. The women went to help prepare the feast of meat and nsima. The children sat on the porches of the houses to wait for lunch. I joined the kids.

I sat on an empty stretch of the clay porch with my camera. Immediately, the children began creeping closer to me. Soon, I was elbow to elbow with a group of ten kids. They were still young, so they hadn’t learned much English, which meant that we communicated in pointing, smiling, and laughing. They enjoyed looking at their reflection in the glass of my lens.

Suddenly, the kids all got up and ran to the back of the house. There had been lots of singing and shouting from all around, but one of the shouts must have been a call to eat. Kenneth, who had quickly become my guide and bodyguard (he wanted to protect me and my camera, even though I had no problem with the children’s curiosity surrounding my gear), led me into the courtyard behind the house where the women and children were eating. The men ate in an adjacent enclosure.

As soon as I entered the courtyard, I was bombarded by requests for photos, which I was more than happy to fulfill. Since it was mid-day, the sun was bright and hot, so many of the people were sitting in the shade of the back porch. This was perfect lighting for some portraits. I couldn’t decide which was my favorite choice to put in this post, so I’ll give you a series of them:

I was thoroughly enjoying photographing the people at the wedding party, but Kenneth told me it was time to go. He led me to the truck and handed me a bowl of meat that the women had prepared for my lunch. I’m not sure why, but they didn’t give me any nsima. Nisar’s wife thinks it might have been because a lot of foreigners don’t eat it. At first, I couldn’t tell what kind of meat it was. It had the same texture and structure of beef, but it was light-colored like chicken. Kenneth pointed to some goats on the side of the road when he asked me if I liked the meat. Apparently, it was goat. It was delicious.

The women followed me, singing loudly and dancing their way onto the truck. When the back was full of singing partiers, we began the journey to the mosque, where we would pick up the bride and groom. About two miles into the trip, the engine died. We coasted to a stop on the side of the road. The drivers told me they had run out of gas, but they took a screwdriver and tinkered under the hood before conceding defeat. The gas gauge in the truck had been reading well below “E” since early in the morning. I had assumed the gauge was broken, but I guess we were lucky we hadn’t gotten broken down much farther from a gas station.

Luckily, someone had brought their bicycle along for the ride. Both drivers and a third man with an old container all climbed onto the bicycle and began pedaling in the direction from which we had just come. There was a gas station right across the street from where the party was being held, so it wouldn’t take them long to get back. The women and children in the back of the truck climbed out so they could sit under a tree. I opened my large reflector inside the cab of the truck to block the hot sun streaming in through the windshield.

Can you imagine what would happen during a wedding in a Western country if the car ran out of gas on the way to bring the bride and groom to the reception…or at any point during the day, for that matter! I see screaming, heart attacks, and maybe a murder or ten. But here, people just shrug and wait in the shade. There wasn’t much else they could have done anyway.

Fifteen minutes later, we were on our way again. The singing recommenced along with someone beating the roof of the truck like a drum.

When we arrived at the mosque, I sent Kenneth to ask the religious leaders if I could photograph inside the mosque. I originally thought I would be photographing the ceremony, but it turned out that had already happened. It had been short and private. I was given permission to photograph the bride, who was waiting inside the mosque. As I started walking towards the building, people in the truck yelled at me. I didn’t understand much, but I recognized a word Kenneth had taught me earlier: sapados. They were telling me that I needed to take my shoes off before entering the mosque. I already knew that, so I told them that I would remove my shoes and signed the motions to calm their worries.

Inside, I found three women, one of which was Hawa, the bride. She was sitting barefoot on a woven reed mat with her shoes on a scarf next to her. Her shoes were pure white, delicately detailed, and looked as if they had never been worn. I asked her if I could take her picture and asked the other two women if they would hold my lights. Hawa seemed very excited about being photographed; this was one of the few times I saw her smile during this otherwise serious occasion. Outside, I photographed Hawa’s new husband and one of the religious leaders. Her husband looked very solemn and didn’t make eye contact with me, preferring instead to look at the floor.

Then it was time to go back to the party. Hawa walked to the truck with one her new shoes on her right foot, but nothing on her left. She stayed like that for the rest of the afternoon. The newly married couple took their seats in the front of the truck while I sat with everyone in back. Again, singing and dancing ruled the truck until we got back to the party.

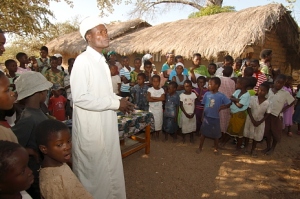

When we arrived, a table and two chairs had been set up under the trees. A group of women all dressed in the same outermost sarong led the couple to their seats. One sarong was turned into a tablecloth. Dancers, most of whom were dressed in matching outfits, lined up in front of the table. The guests, which numbered nearly a hundred and fifty, crowed around the outside. As soon as everyone took their places, the dancing began. The men stomped their feet in unison, swung their arms, and yelled raspy whoops while a small group of men dressed in long, light-blue tunics sang. Kenneth said that there were only a few words sung in Arabic and Chichewa; the rest was a series of repeated sounds, each unique to the singer, that were sung to make music just like one would do with instruments.

After the dancing, passages were read from the quran by uncles, chiefs, and other important members of the community. Kenneth whispered short translations in my ear as four religious leaders gave speeches about the meaning of marriage and the importance of love and respect in a relationship. Both the bride and the groom looked very solemn during the whole ceremony, sitting very still with their eyes downcast. Kenneth told me that their marriage was arranged by their parents and the chiefs of the villages, but that had nothing to do with their moods; this was a serious occasion and they needed to act as such.

Two men came into the circle left by the dancers and dumped water onto the ground. The first dance had kicked up billows of dust that made it almost difficult to see across the circle. The water was an attempt at controlling the dust, but between the kicking from the dancers and the hot sun, the water was soon gone and the next round of dancing fill the air with yellow dirt once more.

The dancing was followed again by more speeches. These speeches were aimed at the families and the community. They were told that they must support the couple in their union and give help when it was needed. A bowl on the couple’s table was then filled with money by a procession of guests, starting with the chiefs, the religious men, and the male family members. When everyone sat back down, one of the boisterous religious leaders looked inside, then declared to the guests that they had not given enough. The dancing started up again while more guests dropped coins into the collection bowl.

This dance was slightly different from the others. It began once again with the men arranged in many rows, stomping, whooping, and swinging their arms. Then they danced their way into two columns facing each other. The dance continued much as it had before until the men started dancing closer and closer to each other. Finally, the two columns almost met. The men all kicked up their legs at the same time, very nearly kicking the person opposite them in the face, then spun around, kicked out behind themselves to hit their opponent in the butt, then danced forward until the columns were back to where they started. They repeated this a few times, and each time was greeted by raucous laughter, shouting, and the Arabic call from the women (similar to the staccato sound associated with Native Americans).

Nisar and his wife had bought a gift for the newly married couple, but since they did not attend the wedding, I brought the gift for them. During one of the dancing sessions, Kenneth announced that I needed to present the gift to the couple. One of the village elders was writing down the names of everyone who gave money or gifts. He wrote me down as “Stefford.” Kenneth, who calls me “Stefan,” told him that I have no last name. I didn’t think I should correct either of them.

The dust from the dancing made me sneeze. Kenneth took this as a sign that I needed to leave, even though I told him I wanted to stay. As the sun dipped behind the low hills, I said my goodbyes to the group of children who had been following me (often touching my camera or stroking my long hair) and followed Kenneth back to the truck.

From what I heard, the dancing and speeches lasted well into the night.

Chirombo Village Pt. 3: The Mill

A few days ago, I visited the mill in Chirombo Village. I arrived in the village early in the morning to meet Stanley, one of the villagers who has been showing me around. Despite the early hour, the sun was already quite hot. I put my folded reflector on my head to shade my face, much to the amusement of the local women, who carry very heavy loads on their heads.

Kids posing in front of the mill. One of them had stickers on her forehead, ears, and the back of her head. Chirombo Village, Malawi.

As we walked through the village, people stuck their heads out of windows and doors and around trees and fences to watch us pass. A few children followed us. At one point, a group of about twenty children on their way to school joined us. They took turns gathering up their courage to yell “How are you madam!”

About two kilometers into the walk, I asked Stanley where the mill was. I worried he was taking me to one of the mills in Monkey Bay, which are located at least six kilometers away. He assured me that it wasn’t too much farther and that the mill was still in Chirombo Village. Still, I was surprised how far it was. Chirombo Village is not very wide, but it is very long. Stanley told me that this is the only mill in the village, which means that some women and girls must walk up to four kilometers each way (if they live on the same side of the mill as me), carrying heavy corn on the way there and just-as-heavy flour on the way back.

Once we arrived at the mill, Stanley talked to the workers in Chichewa, asking permission for me to take photos. The children who had followed us stuck around for a few minutes before reluctantly continuing on their way. The two mill workers agreed to let me photograph the mill, though their approval was somewhat halfhearted.

Again, there was much excitement regarding my equipment. When I set up my tripod inside, the mill workers and a handful of children and women came inside to watch me, unknowingly blocking the things I wanted to take pictures of. I waited for everyone to get bored of watching me doing nothing, which happened fairly quickly when a woman arrived with a large bag of corn.

When the machines started, most of the people left the mill. It took me a few seconds to realize why. As soon as the motor roared to life, a cloud of corn flour burst from every opening of the machine. The vibrations also shook the flour from the rafters, causing it to fall gently on my head and my camera. I was covered almost instantly. Throughout my stay, the children took turns brushing the flour from my hair, my back, and my jeans. I could only take a photo or two before needing to blow the dusting off my equipment.

The busy mill. Workers and customers attending to their duties in the mill. Chirombo Village, Malawi.

There are two machines in the mill. Both of them grind corn into flour, but they do it in different ways. I’m not sure if the outcome of the flour is any different; it didn’t look like it. The closest machine in the above photo grinds the corn, the force of which sends the flour through a pipe and a shoot before it empties into waiting buckets. The second machine simply dumps the flour on the floor under the machine. It was the second machine that was used to grind this woman’s corn. When the machine was shut off, she spent a while scooping her flour back into the giant sack she brought with her.

Since nsima, the main dish of Malawi, is made from corn flour, the mill was very busy. Luckily, a full sack of flour can feed a family of five for almost a month, so the women only have to make the trek to the mill every few weeks. According to Stanley, it costs MK500 (around US$3.30) to grind a full sack of corn into flour and MK250 (around US$1.65) for a half sack (no discounts for bulk!). This was the only woman who used an actual sack. Everyone else brought buckets and tubs of various sizes. There was no bartering over price, so there must be some sort of set price for those containers as well.

The price of making nsima is low, even by Malawian standards. Many of the locals here grow their own corn, but the others have to buy their corn in small one-kilo bags. Future-orientated farmers can grow enough corn every year to last them until the next harvest. Some even grow enough to sell off a few bags and earn some extra money. But there are a lot of families that overcook when food is plenty, often throwing out up to half of what was prepared. Then the corn runs out and they must scrape together enough money to buy corn until the next harvest. In this area, each hectare can produce 12-15 sacks of corn. Fertilized fields can produce around 20 bags per hectare. The harvest season is usually between February and April, depending on the rains, so the locals are still eating well from the recent yeild.

There were only a few minutes during my visit when there were no customers. I took advantage of this time to photograph one of the two men working at the mill. The second one was very interested in watching me, but didn’t want to be photographed. Neither of these men own the mill. The equipment in the mill and the gasoline needed to run them cost a lot of money, so most mills are owned by the upper class Malawians. This one happens to be owned by a government minister who lives in Blantyre (about three hours away).

When the customers picked up again, I moved outside to see how the women prepare the corn for the mill. First, they pour some of the corn into large, shallow, woven baskets. They shake the baskets to remove the dust and dirt from the corn. The clean corn is dumped into buckets so the next batch of corn can be shaken clean. When the buckets are full, they are emptied into the grinding machine, then, if the machine with the shoot is used, the buckets are quickly placed to catch the four.

Since it was mid-morning, most of the customers were women between the ages of twenty and seventy. Most of the younger girls were in school. I did see two young teens at the mill. In traditional Malawian families, the females must take care of the house and prepare the food. These two tasks take priority over everything else, including school. These two girls must not have finished their chores in time to make it to class. If they finished everything quickly, they would probably go to class in the afternoon. The girl in the photograph to the right is even in her school skirt.

The longer I stayed at the mill, the more people gathered to watch me work. Some of the women asked me to photograph them. I started with an old, yet boisterous woman, who then patted me down, asking me for money. I emptied my pockets for her, pulling out cords, memory cards, and keys. When my pockets were empty, I turn them inside out. The old woman thought it was all quite entertaining, and showed the other women all the strange things I had in my pockets instead of money.

One of the women waiting in line for the mill asked me to photograph her and her baby. She stood very still and very strong, holding her child, who started crying when she took him off her back. To calm the child, she began nursing him, but motioned that I should still photograph her. When it was her turn to use the mill, she passed her child to one of the girls who had come to watch me. The girl had been making funny faces at my camera when I photographed her, but when she held the child, she became very composed. The baby stopped crying when my lights went off, and he inspected me and my camera with unblinking eyes.

Finally, Stanley, who had become anxious because of the disruptive crowd that had formed to watch me and to be photographed, decided it was time to leave. I thanked the mill workers and the women I photographed, then headed on my way, followed, as always, by a group of children.

Chirombo Village Pt. 2: The Boat and the Funeral

I went to the village last night in hopes of photographing a man in his canoe, or bwato. (I participate in some online photo competitions, and this week we had to photograph a boat or any sort. I planned on staging the whole thing, so I knew these would not be true photojournalistic photos. They are real people from the village and the boat is a real canoe that they use for fishing, but the location and the poses are staged by me.)

I packed up all of my gear and brought a friend along to act as my human light stand. Along the lake shore, we saw some children playing with dogs and some women washing dishes and clothes, but no men and no canoes. Usually, the reeded area of the shore is full of boats, but it was empty. Out on the lake, there were only one or two people fishing, so I knew the boats must be around somewhere.

Finally, at the main entrance to the village from the shore (which I have only used once—I usually take a short cut shown to me by Stanley) I found a group of men sitting under a tree. One was making rope for his nets while the others chatted. Nearby were a few canoes.

In a cross between English, Chichewa, and sign language, I greeted them and asked if anyone would be willing to pose for me in a bwato. They mumbled quickly amongst themselves before the man making rope stood up and signaled that he would pose for me.

He got into his canoe and I motioned for him to row down the shore a bit until he was in the sun with the island in the background. The men all watched as I set my gear up, and they were particularly impressed by my giant reflector that snaps open on its own.

Using English and sign language, I ran my model through a series of poses. Within two or three photos, I had a big group of people standing around me. Most of them were children who kept jumping in front of my camera. I asked the children to stay out of my picture and promised that when I was done with my original model, I would take their picture too.

I hurried through shooting my original model (whose name I unfortunately can’t remember) and asked him if I could photograph the children in his bwato too. He agreed.

I motioned to a particularly excited three-year-old girl that she could get into the canoe first, but the oldest male child there quickly grabbed her by the shoulder and said some harsh words to her before climbing into the bwato himself.

As so it went. I photographed the older boy children, then the older girl children, followed by the younger boys and finally the younger girls. The children under the age of three weren’t allowed in the boat at all. The teens and adults weren’t interested in being photographed in the boat, but they enjoyed watching me and inspecting my equipment.

The older children looked very stoic and strong in their posing and wouldn’t crack a smile regardless of what crazy positions I put myself in when photographing them. The younger kids on the other hand, especially the girls, were all giggles. Granted, most people think I look pretty silly when I’m taking pictures (I usually perform some intricate contortion moves to get just the right angle), but these kids thought I was absolutely hilarious. Some of them were great actors and would erase their smiles as soon as I brought the camera to my eye, but some of them just laughed and laughed until their sides hurt.

One of the younger girls had a beautiful smile and couldn’t restrain her giggles. I was so enamored by her smile that I easily took four times as many images of her than I did of most of the others.

When I finished photographing everyone who wanted to pose for me, I packed up my gear, still with a large audience watching (again, my reflector was a huge source of entertainment as I twisted it up to fit back into the small carrying case).

I returned to the village this afternoon and saw many of the same kids I photographed yesterday. They called for me to photograph them, but I had told Stanley that I would be back in the village Monday or Tuesday to photograph the mill. I didn’t do that yesterday, so I had to go today.

Before I left, the power went off. One of the neighbors came over to chat with Nisar (the owner of the lodge I’m living at) while he waited for the electricity to come back on. He told me he had heard that there was a funeral going on in the village. I didn’t want to break my word to Stanley, so I pack my gear and set off to the village anyway.

Sure enough, when I passed the cemetery (which I hadn’t gotten close to before, but had seen through the trees) there was a group of men waiting. I asked them if they knew where Stanley was, but they said no. One of them led me to a local house and told me to wait while he went to look for Stanley.

I entered the fenced area around a small brick house and greeted the two women sitting on the porch. They seemed happy to hear me speaking Chichewa and started asking me questions. It wasn’t long before they realized that I had already exhausted my Chichewa vocabulary.

One of the ladies passed her tiny (maybe a week old) baby to the other woman, changed her shirt, then went to help find Stanley. The remaining lady and I sat on the porch in silence. Children gathered on the other side of the fence and peered at me through the gaps.

After a few minutes, I heard singing in the distance. It was absolutely gorgeous, and I could tell it was getting closer, heading towards the cemetery I had passed on my way through. The procession had somehow organized itself into perfect harmony, with some people humming chords, others singing melodies, and a single man calling and chanting his own part that, while very different, wove itself effortlessly into the rest of the song.

I craned my neck to see through the opening in the fence. Luckily, the opening lined up perfectly with a break between the houses across the lane, providing me a tiny glance at the march of the mourners. I saw no coffin and no body, but when the group reached the cemetery, I could hear the mournful wails of what I assumed to be a mother or wife sounding over the singing voices.

Just then, Stanley came into the house’s enclosure with the woman who had left to go find him. After saying our greetings, he explained that the mill was empty today because everyone was at the funeral. He said I could come back tomorrow morning to photograph them. He then introduced me to the women of the house, who turned out to be his sister-in-laws and his mother-in-law (who came out of the house when Stanley arrived).

On my way back, the group of kids I photographed yesterday, bolstered by some newcomers, asked me to photograph them again. There was still some light left, so I agreed. I snapped off some shots with natural light before I pulled out my flash. When the flash went off for the first time, the kids who hadn’t watched me yesterday screamed and ran away or hid behind each other. When they realized nothing bad had happened, they dissolved into giggles.

The Namazizi School, Monkey Bay, Malawi

On Thursday of last week, I visited the Namazizi School (also called the Namadzidzi School). I had visited a few days earlier to get permission to spend a day photographing the classes.

I arrived at 7am, guided by the sound of a beating drum that is used to call the students to school. As they waited for everyone to arrive, a teacher led them in some stretching and exercises. A few minutes later, the morning assembly began. They started by singing the national anthem before they all sat down to listen to the announcements given by the teachers. Stanley (who met me on my way to the school) and I were ushered into the headmaster’s office, but we could still hear the assembly going on. Stanley gave me translated summaries of what was said.

The day before, there had been an important meeting at the school that all parents were required to attend. They were supposed to discuss topics including the future of the school, the progress of the students, and the upkeep of the programs. Among other things, it was decided that the parents would pay MK100 (around US$0.65) for the students to have nsima (like finer, stickier polenta, or a corn-based porridge/paste that is the base of Malawian cuisine) at school. The problem was that not all parents were at the meeting, despite the mandatory attendance. The teachers told the students that if their parents had not attended, they were to leave school and force their parents to come. They would not be allowed back in class until their parents came to the school to learn all that was discussed at the meeting. The students nervously laughed and balked at the thought of forcing their parents to do anything, but sure enough, when the morning assembly was over, students filed both into the classrooms and out of the courtyard, towards the villages.

Because of excitement of the morning’s news (and the arrival of a mzungu girl with a backpack full of camera gear), it took a while for the courtyard to empty and the classes to begin. Since so many of the students had left to fetch their parents, the headmaster decided that I should wait to begin photographing the classes. She didn’t want the classes to appear empty, but I suspect that the absent students and teachers also didn’t want to miss the chance to be photographed.

The headmaster told me that the only class that was full was one of the lower grades, but she did not want me to sit in on that class because it would be taught in Chichewa only. Despite my reassurance that the language didn’t matter, and my joke that the languages didn’t show up in the photos, I was still told to wait until the classes were ready for me.

So I sat in the headmaster’s office and photographed the posters on the wall and the occasional student who came to peak at me. Hanging on the wall was a plaque that said that the school had won an award for the best kept school a few years back. On the board to the left were all the school schedules listing who taught when and what each class would study every day. According to those schedules, the classes studied by the older students, which I would be photographing, are English, Chichewa, mathematics, social and environmental sciences, science and technology, expressive arts, agriculture, and life skills. The board to the right talked about the PTA (Parent-Teacher Association) and other school organizations.

I continued to sit in the office well after classes started. I could hear the younger students next door chanting the alphabet and the sounds of each letter. When song broke out, Stanley told me that the students were embarrassing someone who had shown up late to class. Every once in a while, I would hear lots of loud laughing and shouting. Stanley told me that the students were chiding one of their classmates for failing something.

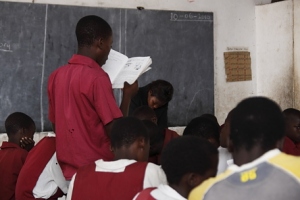

After a few hours, the heat and the chanting started lulling me to sleep. Finally, around 10am, I was told I could photograph standard/grade 6. I was marched across the courtyard and into the classroom, where the students promptly stood up, chanted “Hello madam! How are you!”, waited for my response, then sat back down in unison. Quite a greeting. The teacher walked in behind me, and she was greeted in the same way.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.The first lesson I photographed was agriculture. The students were learning about different types of irrigation, which plants grew best with which type, and why it is important to irrigate crops. They broke into groups to discuss each part, then gave a summary of what they talked about. In between listening and writing, the students tried to slyly watch what I was doing. When they thought I wasn’t looking, they would point at me and whisper furiously, breaking into laughter and hiding behind their hands when I caught them.

Next was mathematics. The teacher began by having all the students stand up and asking them multiplication questions. When a student answered a question correctly, he or she was allowed to sit down. The rest of the class would clap for each right answer, always the same beat and always in unison: clap-clap-clap! clap-clap-clap! clap! clap! clap! clap! It’s pretty impressive (and slightly daunting) to watch and hear nearly 50 teens react in unison. It reminded me of the military.

I thought I would be spending the whole day with the same class, but since it was such a special occasion to have a photographer at the school, all the classes wanted their time in front of the lens. But the headmaster had only ok’d one other class. After taking a portrait of the teacher of standard 6, I was whisked away to the next group.

Again, upon my entrance into the classroom, the whole class stood up, chanted their greetings and welcomes, then sat back down in unison. They didn’t tell me which year the class was and I didn’t want to interrupt to ask, but they were mostly between two and seven years younger than the students in the other class.

They were just about to begin their English lesson when I arrived. The teacher held up hand-written cards with vocabulary words on them and asked the students to read them. When she exhausted the pile, she instructed the students to open their reading books and read to themselves a short story. When they had finished, she helped them critically analyze the story and answer comprehension questions.

The story was about two students, one male and one female, who were in school preparing for the examinations that would decide whether they were eligible to attend university. The boy wanted to become a pilot (one of the vocab words) and the girl wanted to become a doctor. The girl’s parents told her that she didn’t need to take the exams because girls weren’t allowed to become doctors. The teacher discussed gender equality with the class and explained that any of them could become anything they wanted, no matter whether they were male or female.

I had gotten the impression throughout the morning that the topics of the lessons had been chosen for my benefit and to show the school the way they thought I, as a westerner, a mzungu, would expect a proper school to operate. That story may or may not have been chosen for that lesson that reason, but I was still very happy that the story was included in their thin reading book. I wouldn’t mind seeing more first-world schools encourage their girls more as well.

To finish up the English lesson, the class studied conjunctions. The students answered the questions very quickly and would have put most native English speakers (who, from my experience, can rarely even define “conjunctions”) to shame. This lesson was tied into the same story they had just finished reading, so many of the sentences in the exercise were about attending school frequently, studying hard, and choosing ambitious careers.

Throughout the lesson, giggles trickled through the windows. Students from other classes were sneaking from their rooms to sit under the window sill of the room I was in, sneaking glances when they thought I wasn’t looking. Inside, the students also watched me intently. They dutifully returned to their work when I pointed my camera at them, looking very studious for the photos, but they returned to gawking when I photographed someone else When I pointed my camera in the direction of the kids outside, the windows quickly became full of faces pressed against the slats, hoping to get in my photos. I only snapped off a few shots because they starting making a lot of noise. I knew my presence was disruptive enough, so I didn’t want the kids outside to create further distractions.

When the English lesson was over, I decided it was time to leave. I had already finished the liter of water I had brought with me and my stomach was voicing its emptiness. The classroom was stifling hot because very little breeze made it through the slatted windows. Between the heat, my hunger and dehydration, and the weight of my gear (I definitely over packed), I was already feeling slightly weak and very tired. I thanked the headmaster and all the teachers before setting off with Stanley on the half-hour walk under the midday sun back to where I am staying. My remaining energy only barely got me to the bar, where I immediately downed a liter of cold water. (If the winter heat takes such a toll on me, I’m pretty sure I’m going to die come October when the real heat starts.)

Overall, I think the shoot was successful. I got some absolutely gorgeous photos of the students, but there isn’t enough room in this post to show more than those that tell the story. At times it did feel like I was photographing a well-choreographed play instead of a normal school day, but I’m sure that’s just because having a photographer at the school was such a novelty and they wanted to look their best and be on their best behavior.

I’m hoping that the next time I go to Lilongwe or Blantyre, I can print some of the photos I took at the school. I want to bring the photos back to the teachers and students so they can see what I have done and so they will feel more comfortable granting me more access to the classes in the future.

Chirombo Village Pt. 1

Since I’ve been living on Chirombo Bay for over a month now, I figured it was time for me to actually visit the village nearby. I’ve walked along the shore a few times, but I hadn’t actually entered the village.

Today, I walked along the water, stopping to photograph some women washing clothes and pots in the lake. They laughed and talked to me in Chichewa and I responded in English. Although neither of us understood the other, we had a good time.

Further along the shore, I photographed some men fishing. They were just leaving to go out on the lake, so I couldn’t talk with them for very long. As I photographed them, some boys about 100m away saw me and called to me. I was surprised they saw me–I was standing in some reeds behind a tree–but there are so few azungu (white people) in the area that they get very excited when they see one.

I went over to the boys and asked if I could photograph them. Their English wasn’t very good, but they responded in Chichewa with one of the few words I have learned: “Jambule,” or “Take my picture!” I motioned for them to stand in the shade (shade is beautiful light for photos, but it’s also much nicer on my burnt shoulders). As I did earlier in the day, I chatted with them in English while they talked back in Chichewa, even though we only understood a few words of what the other was saying. After some photos (in the various locations the boys led me to!), I told the boys that I wanted to see the village. It took some sign language and pointing on my part, but they soon happily led me up the dirt road to the village.

Within a few seconds of my arrival, a crowd started to form. The adults peeked out of buildings and the children crept to within a few meters of me. One man approached me and began asking me about myself. I asked if he could show me around the village, but he was the only one working at a nearby shop, so he declined.

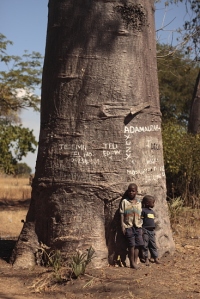

I wandered over to a baobab tree I had passed when I entered the village. I was intrigued by the writing that covered the lower portion of its trunk, which I was later told listed some of the important members of the village. I approached a group of men under a tree a few feet away who were discussing the future of the village and those who lived there. One of the men who spoke very good English, Stanley, gave me a tour of the village.

We started at his house, where I met his mother and two children. He then showed me where he brews his “beer.” From what I have heard from others, it’s not so much “beer” as it is “nearly pure alcohol.” Supposedly two shots can make hefty German men pass out. I was also told that there are some pretty gnarly things in some brews, such as batteries.

But according to Stanley, the ingredients are only water, sugar, and corn. He lets the mixture sit for three days before he puts it in his distilling contraption where it is boiled. Somehow (he had difficulty explaining this part) the alcohol leaves the pot, flows down the tube in the log, and drips into a waiting bottle by way of a strip of reed.

Near the alcohol distillery, there was a strange, small hut on stilts. When I looked inside, I found pigeons. I asked Stanley what he used them for, but he said they are like flowers and are only there for beauty.

Next, he took me to the local school. I talked to the headmaster, and she gave me permission to spend Thursday morning photographing the school. I’ll be photographing the oldest students because I am hoping they will be less distracted by me and my camera than the younger children. We’ll see!

Best Store Name Ever

Unlike most people, I don’t mind spending hours stuck in a car. I’m easily entertained by looking out the window. Driving around Malawi and most of southern Africa is particularly fun because of the gems of store names that abound in these parts. I’ve seen some amazing names, but a few weeks ago, I found the winner, the best in all my trips to Africa. When I drove by again the other day, I had to stop for a photo. I present to you “People Always Complain Hardware.”

I’ll be posting more examples of the incredible store names as I photograph them.

Unlike most people, I don’t mind spending hours stuck in a car. I’m easily entertained by looking out the window. Driving around Malawi and most of southern Africa is particularly fun because of the gems of store names that abound in these parts. I’ve seen some amazing names, but a few weeks ago, I found the winner, the best in all my trips to Africa. When I drove by again the other day, I had to stop for a photo. I present to you “People Always Complain Hardware.”

I’ll be posting more examples of the incredible store names as I photograph them.

Trip to Lilongwe

I visited Lilongwe this last weekend to advertise my photography business at a fair held at the Bishop Mackenzie International School. The weekend went well, especially on the business side of things–I will be shooting and helping advertise a new branch of a popular bar in the city and I might (still working on it!) be photographing 65 students at a daycare.

The rest of the weekend included drinks at the bar mentioned above and a braii/barbecue. Leave it to me to find any Italians or Italian speakers within 100m, as I did at both places!

The most interesting part of my trip (as in the most interesting for you all to read about) would be the bus rides from Monkey Bay to Lilongwe and back. By car, one can get between the two in about 3 hours. By bus, it takes over 5 hours. There is a sign at the front of the bus that says the occupancy maximums are 65 people sitting and 25 people standing. If you count all the children that sat of various laps, there were probably 75-80 people sitting at any given time and 35-40 people crammed into the aisles–and that doesn’t include the luggage and person-sized bags of corn, beans, and flour that were stacked anywhere they would fit.

On my way to Lilongwe, I had someone sit on my lap, someone sit on my shoulder, someone use my head as an arm rest, and a baby tried to pull my shirt down to nurse. When I recounted this to Dida, the lady who graciously let me stay with her family that weekend, she laughed and said,”Well, that’s part of the African Experience, I guess…even if most Africans never go through that!”

The ride back was much more manageable. I decided to sit on top of a stack of bags full of various foodstuffs, which put me too high for people to sit or lean on. It was also cloudy. Sometimes a lack of sun beating on you can make all the difference!

I had intended to take a picture of the Lilongwe skyline, but I’d forgotten that the city doesn’t really have one. There are a few hills and a few multistory buildings, but nothing close together enough or prominent enough to be called a definitive “skyline” or “cityscape” in the way that most other large cities do. Instead, I’ll leave you with a landscape that I took on my way home. It’s nothing spectacular since I actually shot it through the window while the bus was in motion, but it will give you an idea of the beauty I got to look at for a few hours this weekend.

3 comments